The culturally subversive content of Boccaccio’s Decameron continues to unnerve and divide scholars. What would inspire, in the middle of the 13th century, a work so marvelously anomalous, groundbreaking and alive? What would cause it to spread into an area in which religious forces continued to convey and control the ideas of authors such as Petrarch; indicating that the fourteenth century willed predominately to identify itself as a journey filled with tension regarding the renewal of Christianity and the attacks of Catholics who would eventually participate in the Scisma[1]?

The cultural and not ideological flaws, from which this identity derived, are revealed in the Decameron. The liberating and vital spirit that fill its’ pages appear almost heretical compared to the works of its contemporaries; and the Decameron has played against this since the time of its publication, as the fame immediately achieved by the work made Boccaccio an affirmed name. What did Boccaccio do then? He included an encrypted message in his 100th Novella through the creation of his character Griselda, one of the works’ most anomalous characters.

Griselda endures all of the abuse and insults, which a destiny of unhappy marriage reserved for her, by the hand of her cruel husband with humility. When the reader meets this character he does not perceive her to be a “Boccaccian” woman.

The reader who is aware of the correspondence between Boccaccio and Petrarch often asks why Boccaccio seems to be seeking through his Griselda a type of validation of the Decameron; a validation that would grant a pre-absolution from the severe judgment that that Church could have given his work.

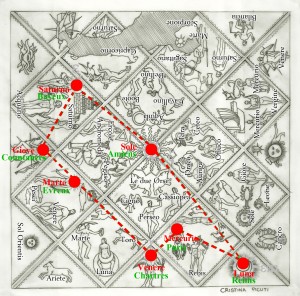

In her book, Boccaccio, L’Enigma della Centesima Novella, Patrizia de Santis attempts to answer these difficult questions. She reveals that Griselda, the most mild and resigned Character of the Decameron is actually an allegory meant to be interpreted in the exact opposite manner. According to de Santis, this is revealed through a series of hints and references which Boccaccio in a hidden but profound manner, spread throughout his Novella. These same references contain a message that might refer to the brotherhood of Girolami, which Boccaccio may have belonged to, (as was speculated by the scholar Renzo Moretti in 2005) having been appointed in 1334 to prevent the loss of the knowledge acquired by the order before their suppression twenty-two years beforehand. These theories are confirmed by a cycle of alfresco, related to the novella, in a Northern Italian castle. Twenty four paintings contain a map of the stars which serve to preserve the symbolic value of Griselda as an icon, according to de Santis, of the Graal; which would allude to the name chosen for her.

[1] Scisma- Italian word referring to a movement in the earlier centuries of the church by Catholics who due to a difference in opinion of the Catholic doctrine, broke away from the church to form their own religious communities.

By Giovanni d’Alessandro

Source: Il Centro